125 years ago today: NZ’s deadliest industrial disaster

Today marks the 125th anniversary of our country's most deadly industrial disaster, the explosion at Brunner Mine that killed 65 men and boys.

Now a popular stop near Greymouth, Brunner Mine Historic Area on the West Coast is the site of the worst mining disaster in New Zealand’s history.

It was about 9:30 am on the morning of 26 March 1896 when a sound like artillery fire was heard throughout the bustling coal mining town of Brunner in Westland’s Grey Valley. Some people saw smoke. But there was no obvious damage to the buildings at the entrance of Brunner Mine. This told would-be rescuers that the explosion had happened somewhere deep inside.

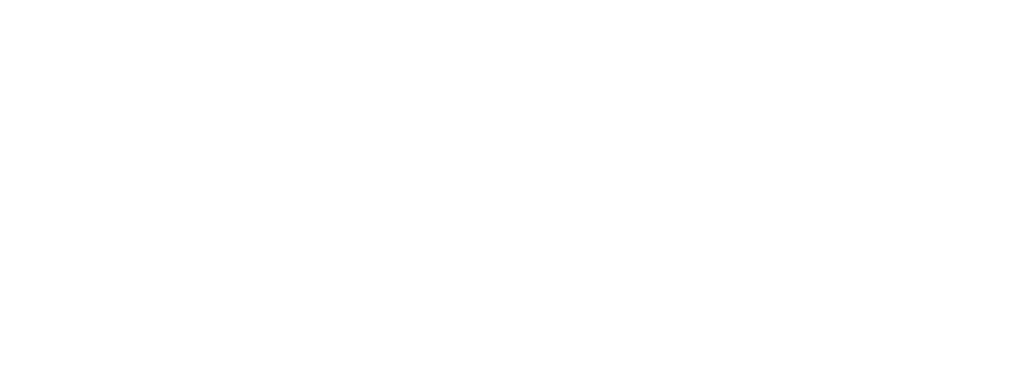

The seam of exceptionally high quality coal that miners were following into the depths had been discovered by explorer and surveyor Thomas Brunner in January 1848. By the 1880s Brunner Mine on the banks of the Grey River was the largest coal producer in New Zealand and had associated works such as a railway bridge, an ever expanding settlement, and other industries including brickmaking and coke production.

View of the coalmining town of Brunner, showing the bridge and mine. Image: PA1-0-498-36, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ

Following the explosion, a crowd gathered while the manager and the underground engineer went down to check what had happened. When they didn’t return, miners from other shifts followed them, only to find the two men unconscious from afterdamp. Afterdamp is the miners’ term for a deadly mixture of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen and other gases following a coal mine explosion.

Despite the risks of afterdamp, the rescue party moved further into the diggings. They could only work in short shifts, and many men were brought out unconscious. However, they were determined to find the bodies - and any survivors - and insisted on returning to the airless mine as soon as they’d been revived on the surface. Unfortunately some of the men’s lungs were permanently damaged, which meant that they could never work again.

From 11 am the rescuers began bringing out the bodies of dead miners. When the rescue parties moved deeper into the mine they found signs of a huge explosion. The railway line and trucks were twisted and smashed, and some of the bodies recovered were so badly mutilated that they had to be identified by their clothing.

As news of the disaster spread, groups of rescuers came from Blackball, Greymouth, Westport and other parts of the West Coast. The miner’s code was strong, and it dictated that they come to each others’ assistance. Among them were mine managers and workers, former workmates, relatives and friends who belonged to the same generation of immigrants.

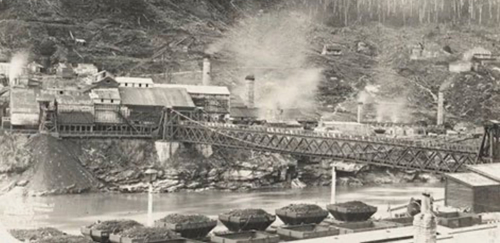

On of the first bodies recovered from Brunner mine. Image: Christchurch City Libraries, PhotoCD 2, IMG0072)

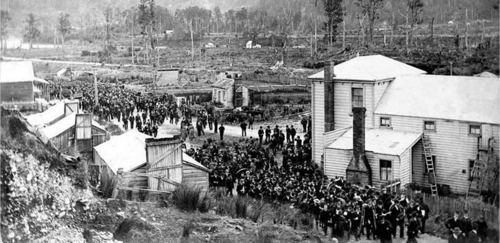

By 2 pm the day after the explosion 64 bodies had been brought out of the mine. It took a further three days to locate the last body. A total of 65 miners died in the disaster, almost half of the Brunner underground workforce. Among them was a Mr. John Roberts and three of his sons, who were all working that day. 53 of the victims were buried in nearby Stillwater cemetery, 33 of them in a single grave. It was estimated that the funeral procession, which stretched for half a mile, was made up of around 6,000 people.

Brunner Mine disaster funeral procession, which stretched over 800 metres. Fifty-three of the victims of the Brunner mine explosion were buried in the Stillwater cemetery, 33 of them in a single grave.

There were varying views as to whether it was the explosion or the poisonous gases that killed the miners. Joseph Scott, the Blackball Mine Manager, believed that the majority were killed by the explosion. Others believed that it was the afterdamp. Dr. James McBrearty’s description of many victims frothing at the mouth suggests asphyxiation by the predominant afterdamp gas, carbon dioxide. It was not then fully appreciated that only small quantities of carbon monoxide (also known as whitedamp) could be fatal.

The disaster and the plight of the families caught the attention of the whole nation. 42 women lost their husbands and 112 children lost their fathers. Many families faced eviction because the mine company owned their homes and these were needed for replacement workers. A disaster relief fund for the miners’ families was launched the day after the explosion and money was given from all parts of New Zealand. Altogether more than £32,000 was raised for the fund. These days this would be the equivalent of almost $6.5 million!

Who was to blame for this tragedy? It seemed most likely that the explosion was caused by firedamp, a common hazard in coal mines, where a pocket of methane gas is accidentally ignited and explodes. The miners believed the cause of the explosion was ineffective ventilation. The official government inquiry determined that a charge had been placed the wrong way around in a part of the mine where there should have been no one working. The mining company was cleared of any negligence, and Brunner Mine continued to operate until 1906. Coal mining from the greater Brunner lease area ended in 1942.

In the decades that followed, Brunner and subsequent mine disasters spurred significant changes in our society including stronger unions to give a workers’ voice, political parties that better supported workers, and improved safety legislation.

One hundred years after the disaster, in 1996, a statue of a miner was erected at Brunner, recording the names of those who died in the explosion and others who perished from mining accidents. Image: Jason Blair

These days you can walk through the industrial ruins on both sides of the Grey River, which are joined by a classic suspension bridge. Allow at least one hour to explore the large and diverse range of mining remnants, beehive coke ovens, brick factory and tunnel entrances all set in a lush green setting, 11 km east of Greymouth on SH7.

Brunner Mine is proudly cared for by the Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai, and has been recognised as one of 25 Tohu Whenua, places that capture defining moments in Aotearoa New Zealand’s story.